In a previous post, we discussed the benefits of the micro oxygenation technique. In this post we’ll discuss the essential principles and its limiting factors.

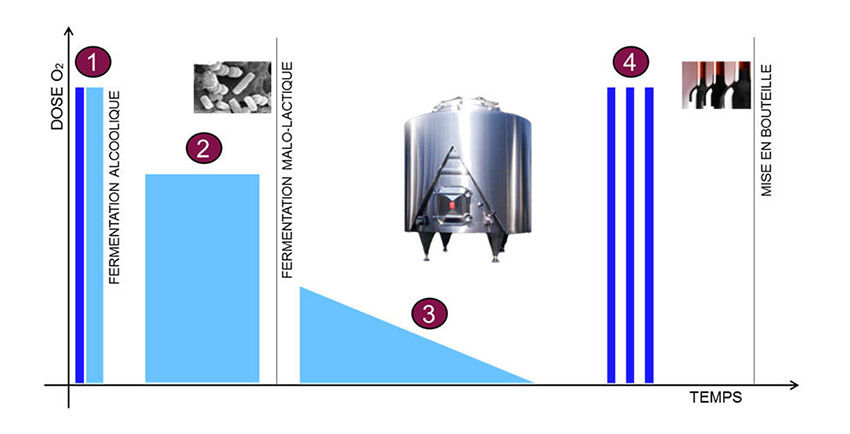

Oxygen can be added at various stages of wine development, considering that the objectives and method of use will bne different on each occasion:

- During alcoholic fermentation (phase 1)

- Between alcoholic fermentation and malolactic fermentation (phase 2)

- After malolactic fermentation or aging (phase 3

- Before bottling (phase 4)

In phase 1 and phase 4, oxygen is added intermittently (or abruptly) for the needs of the yeasts and to prepare the wines for their time in the bottle.

Figure 1: The different phases of abrupt or controlled oxygen addition. (Source: Vivelys)

Figure 1: The different phases of abrupt or controlled oxygen addition. (Source: Vivelys)

We distinguish the contribution before malolactic fermentation (MLF) from the contribution post MLF because the same results cannot be obtained and it is not applied under the same conditions.

Before MLF, the contribution of oxygen allows the structure of the wine to be designed, and after MLF it will be the base of the wine.

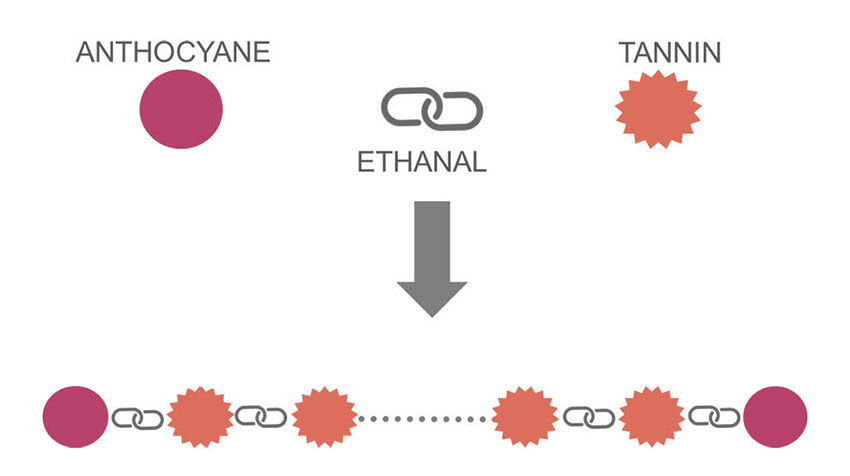

In this design phase, the supply of oxygen allows the creation of complex polymers between anthocyanins and tannins through an ethylene bridge (ethanal) as indicated in the following figure:

Figure 2: Principle of tannin-anthocyanin polymerization with the ethylene bridge. (Source: Vivelys)

Figure 2: Principle of tannin-anthocyanin polymerization with the ethylene bridge. (Source: Vivelys)

Ethanol production is a key element for the use of micro-oxygenation. It must be produced at a sufficient quantity, but not in excess, as it could be detrimental to the quality of the final wine.

Microoxygenation control, therefore, depends on the user's ability to perceive ethanal, the description of which varies depending on the concentration in the wine, from a cocoa powder profile to roasted apple.

In addition, depending on the concentration of tannins and anthocyanins, it is possible to obtain completely different polymers and results.

In case of imbalance (T/A> 4/1) the oxygen supply leads to a longer polymerization and the impact on the wines is different, always trying to limit negative sensations such as dryness and color evolution towards yellow tones.

In the opposite case, when we have a favorable ratio (T/A = 4/1) the polymerization is more limited and the impact on the wines is positive (more red color, more fat and better resistance to oxidation).

The Tannin/Anthocyanin ratio is unfortunately not stable over time and tends to increase during the life of the wine due to the extreme fragility of the anthocyanins. Therefore, it is necessary to try to rebalance this relationship as soon as possible through an early blend.

There are 2 limiting factors to take into account when applying microoxygenation to a wine:

- Temperature

- Turbidity

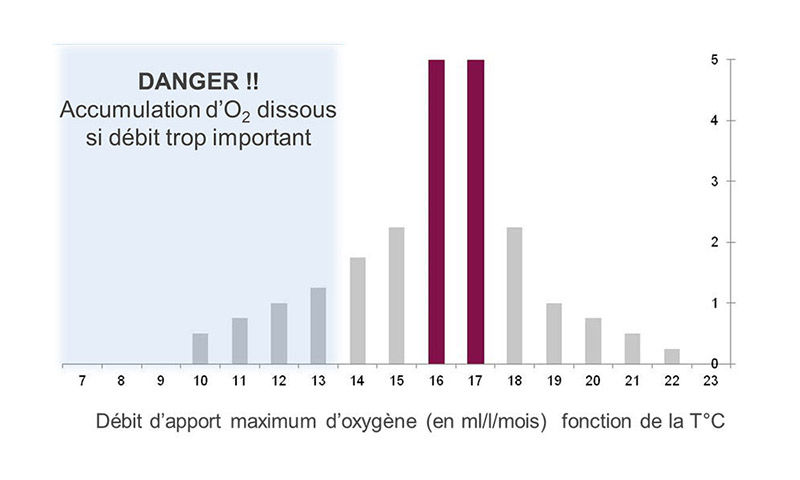

The temperature directly influences the dissolution of gases over liquids, that is to say the dissolution of oxygen in wines.

The contribution of oxygen to wines that are too cold can cause an accumulation of a high amount of oxygen, which, consequently, can lead to significant oxidation when the temperature rises.

For this reason, a temperature must be maintained between 16-18 ºC or the oxygen supply must be reduced, all depending on whether we are at low temperatures.

Figure 3 shows the dose limits that should not be exceeded as a function of temperature.

DANGER! Accumulation of 02 is the dose is high

Figure 3: Maximum oxygen dose (mL/L/month) based on temperature. (Source: Vivelys)

Figure 3: Maximum oxygen dose (mL/L/month) based on temperature. (Source: Vivelys)

Another limiting factor in the addition of oxygen is turbidity.

In fact, the oxygen consumption of the lees, during the fermentation phase, is a factor to be considered. This can interfere with the goal of contributing to the creation of Tannin/Anthocyanin polymers.

Therefore, it will be necessary to clean the wines sufficiently (between 100 and 200 NTU) at the end of AF to reduce the amount of lees.

® Vivelys

Related news

What are the benefits of microoxygenation?

Controlled oxygenation allows the profile of the wine to evolve. It has multiple effects and affects the color, aroma and structure in the mouth of the wines.

Oxygen: friend or enemy?

These days, with the level of knowledge that we accumulate of all those reactions in which O2 plays an important role, we are clear that the management of this element in the winery is essential to be successful in obtaining the target wine profile.