A stylist is the professional who analyzes you and decides how to enhance your virtues and hide your flaws so that others like you. Wood does the same with the fruit we have obtained from the grape with care and affection. Therefore, aromatic expression is the first thing that comes to mind when we talk about the involvement of wood in wines.

But first of all we must remember:

- that not all wines are suitable for barrel aging.

- And the result of the same wood depending on the wine can be totally different.

Therefore, they are the first criteria to define. We need to know the tannin/anthcyanin content of the wine for aging and the balance between both. The concentration of these two compounds should be greater than 2.2 g/l of tannin and greater than 500 mg/l in anthocyanins; in case of not reaching these parameters the T/A ratio shouldn't be more than 1/4.

If a wine is rich in anthocyanins but it has little tannin, initially there will be good polymerization between the two but the leftover anthocyanins will quickly oxidize causing color precipitation and leaving the wine light and totally unprotected. However, if the tannin concentration is very high in relation to the anthocyanins (>1/5), these tannins will polymerize with each other, giving the wine a more tile color and excessive astringency.

If the anthocyanin and tannin concentration is correct the aging will be adequate obtaining meatier wines in the mouth, good balance between fruit-wood and good harmony.

The analysis to calculate the concentration of these compounds is essential but also good training in sensory tasting to get to know the balance of these compounds in the mouth. We often taste wines that despite having the same concentration in tannin or IPT, some are harmonious; while others are totally aggressive and astringent. We must remember that a wine is not better the more astringency it has to age, but better the more harmony it has. Therefore, in addition to analysis, tasting is also essential. This helps us to determine the different types of tannins in the mouth: green (reactive), hard or dry. We cannot quantify these sensations with analytics, and they are important for the aging of the wines, because depending on the type of tannin the wine has, aging will go in one direction or another.

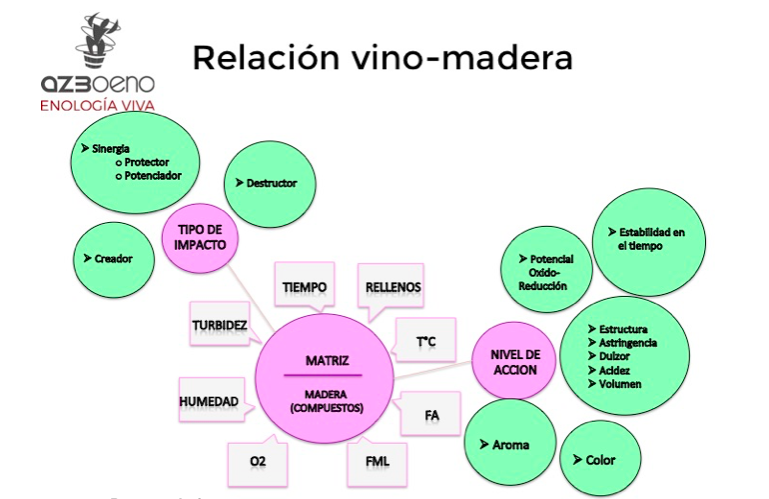

Another aspect to take into account is that the same wood depending on the matrix (wine) can produce a completely different result and of course also affect the style of wine we want to create. To do this, as an example, we could indicate that:

- To mask the vegetal, we must work with wood that provides a high concentration of vanilla and whiskey lactone.

- In order to respect the fresh fruit or to refresh the ripe fruit, we must work with wood poor in whiskey lactone and with higher toasting from M+ e and even with toasted bottoms if it is an American barrel.

- To ripen the fresh fruit, medium toasted barrels and, if using American oak, also toasted M, but on this occasion, the bottoms not toasted.

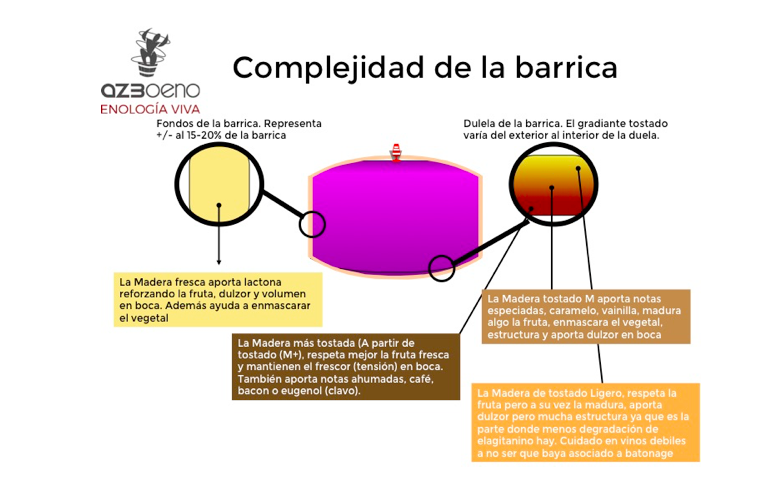

Complexity of the Barrel

Fruity, floral, spicy, vanilla or toasted notes complete or build the aromatic palette of the wines. These aromas come either from the degradation of wood compounds during toasting, or from the wood itself:

The volatile compounds in wood are numerous but in low amounts; they represent only a small percentage of the compounds of the wood. The eugenol provides spicy characters, the ß-ionone floral characters, the lactones milky and fruity notes. Untoasted woods are aromatically less intense than toasted ones, and can work on the volume in the mouth, limiting the aromatic impact and reinforcing the fruit. These lactones mainly come from the bottoms of the barrels, which in the case of barrels represents approximately 20% of the exchange surface. In this case, it is necessary to be careful with the quality of the wood, since poor drying provides "green woods" with sawdust, drying and vegetable characters.

Lignin degrades during roasting giving rise to volatile phenols and aromatic aldehydes (guaiac, vanillin, syringaldehyde), at the same time as hemicelluloses give furan compounds (furfural, 5-methylfurfural: notes of nuts and toasted almonds). Each aromatic compound appears preferably at a specific temperature. A mixture of different toasting temperatures provides complex woods, allowing the style of wine to be defined between intensity and complexity.

Alcoholic and malolactic fermentations change the aromatic profile of the wood. In addition to the absorption of volatile compounds by microorganisms, which reduce the aromatic intensity, there is also a transformation of certain molecules: vanillin is transformed into vanillic alcohol, almost odorless, while furfural can give rise to furfurylthiol. This compound often appears when malolactic fermentation takes place in the presence of barrels rich in furfural.

Aging in wood in synergy with the barrel's own micro-oxygenation, generally increases the color of the wines, the desired effect in the case of red wines. This effect is greater the earlier the wine enters the barrel. This effect is linked to the tannic contribution and/or to the colorings. Tannins react with the anthocyanins by co-pigmentation at the start of aging.

Related news

How to prepare the wine for aging. (part 2)

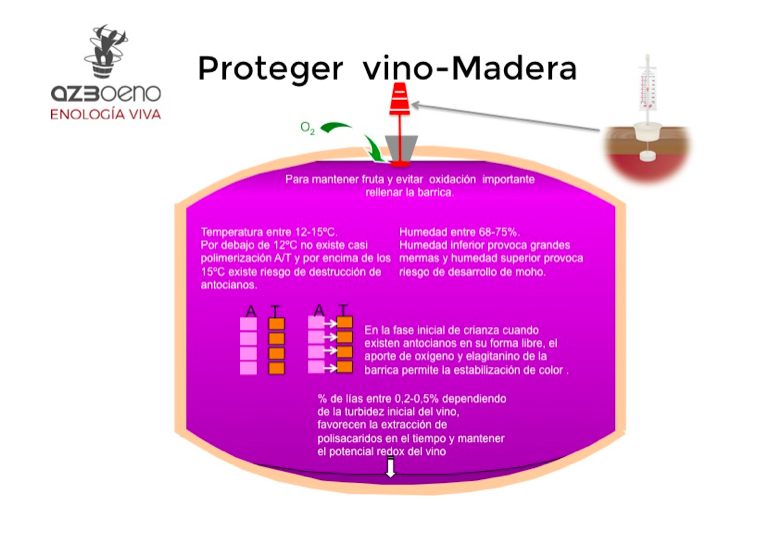

Protect the fruit

It is up to us, the winemakers, to modify and/or control all the physical-chemical, biological and sensory transformations during the aging of the wine in the barrel, depending on the wine we want to market. Therefore, we set out some essential aspects for proper management of the wine in the barrel.