Last March, we toured a large part of Spain with the aim of demystifying one of the most frequent topics in enology: the dryness of red wines.

In this article, we will discuss the mechanisms and parameters that cause this dryness. We will talk about the role of variety, maturity, vineyard stress, extraction, aging and contamination.

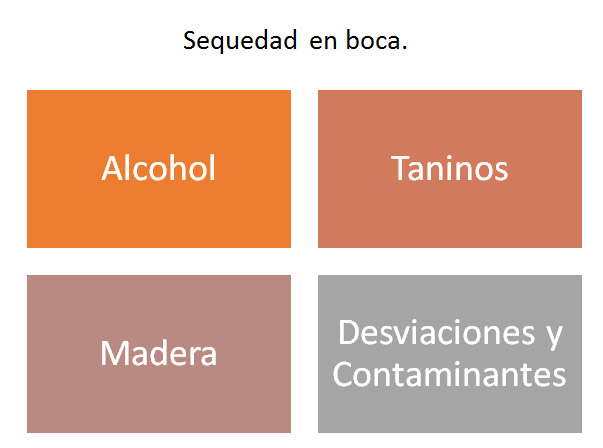

It has often been thought that the dryness of wines is caused by tannins, however, the reality is not so simple. Dryness can appear due to various factors such as excess maturity (burning effect of alcohol), wood, the extraction of tannins during the fermentation of overripe grapes and due to contamination or microbiological diseases.

In this article we will develop the dryness caused by alcohol and tannins, although in a later article we will continue to analyze the dryness caused by wood and pollutants.

The dryness of alcohol

Winemakers who practice dealcoholization of wines are well aware of what North Americans call the & nbsp; sweet-spot, that is to say the optimal alcoholic strength the wine should have to perceive the sweetness of the alcohol in the mouth without feeling the fiery nature. It is that ardent and drying character of alcohol that we are going to focus on in this first part.

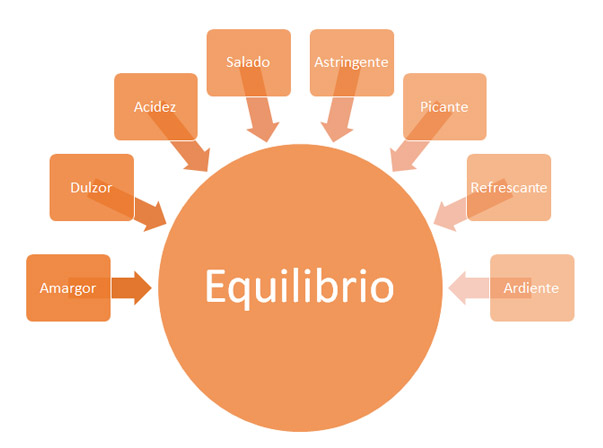

The perception of wine in the mouth is divided into two chemical dimensions: taste and the touch. The effect on the tongue, which is defined by taste, includes the elemental flavors (acid, salty, sweet and bitter) while touch brings together three of the sensations that participate in dryness: refreshing astringency, burning and metallic.

The chemical sensations are related to each other. It is important to define the ambiguous character of these descriptors. The fiery character of the alcohol and the spiciness will reinforce the sensation of dryness of the wine.

When the wine passes through the mouth, it is not about achieving a succession of sensations, but a balance between all of them so that they are linked together: the spicy reinforces the astringency and the fiery increases it, but in a negative way (dryness), on the other hand, the sweetness inhibits the astringency. Thus, all together they form a balance that creates a global perception.

Just as there is no single sweet sensation or pure sour sensation, there is no single astringency. Acid can be green when it comes to malic acid, hard when we talk about tartaric or bittersweet in the case of lactic acid.

In the same way, the astringency can be tannic coming from grape tannins, wood or coming from other toasting molecules. As it does not have a single form, the taster always has to specify which of these origins it comes from.

Astringency participates together with alcohol and acidity in what we define as the body, relief structure or skeleton of the wine. This structure, acidic for white wines, is mainly fiery or astringent for red wines and always causes more or less aggression in the mouth.

The enological trend in recent years, where the grape is harvested with a higher alcoholic strength, is caused by the need to achieve a loss of reactivity (greenness) of the tannins. This reactivity forces winemakers to carry out comprehensive aging to allow the tannins to ripen by polymerization with oxygen.

During the grape ripening process, the tannins polymerize with polysaccharides, losing their ability to react with proteins and oxygen. The winemaker always seeks greater physiological maturity to have less reactive tannins, less greenness and subsequent reduction.

This tendency to harvest at high maturity, modifies the extraction practices during fermentation, preferring extraction in the aqueous phase to extraction in the alcoholic phase. It is not the same to discover a density of 1020 for a wine with a potential of 13º or 15º.

To limit the solvent effect of alcohol, and to have a balanced extraction between tannins and anthocyanins, we must limit the drainage with long pump-overs. The alcohol flow extracts tannins from the seed.

In the case of high levels of alcohol, it is also important to have good fat extraction (polysaccharides). In this case, we must extend the maceration with time and temperature, but with no mechanical action. It is important to mask the burning structure with viscosity rather than with any other form of additive.

The sulfur in the vat also has a high solvent power that ireinforced by the alcohol. The use of high doses of sulfur comes from regions where extractability from the grapes is very low. Therefore, the idea of reducing sulphite in the vat so as not to force the diffusion of excessive tannins is also an option to consider.

Sulfur and alcohol, good preservatives, bad solvents.

Dryness due to tannins

If the technicians are interested in the extraction of tannins from an evolutionary point of view of the wine, the consumer is interested in the balances of the wine.

We often taste wines that, despite having the same concentration of tannin or (IPT), some turn out to be harmonious while others are totally aggressive and astringent.

If a wine is rich in anthocyanins but has little tannin, there will be good A-T polymerization, but the excess anthocyanins will oxidize quickly, making the color fade and leaving the wine light and unprotected.

If the anthocyanin/tannin concentration is correct, we will obtain wines that are meatier in the mouth and have a good balance.

However, if the tannin content is very high to the anthocyanin ratio, these tannins will polymerize with each other, turning the wine into a more tile color and giving it excessive astringency.

Once the tannins (flavanols) have been extracted, they polymerize among themselves to achieve more polymerized and therefore more astringent molecules. This is what we call oxidatiuve polymerization with an increase in the final dryness. The only way to slow down this oxidative evolution is the presence of anthocyanins in sufficient quantity to condense with the flavanols and form more stable colored polymers.

In addition to the chemical perception of astringency, tannins react with proteins in the mouth, mainly mucin and proteins rich in proline (PRPs), to form a precipitate that inhibits the lubricating power of saliva. This precipitate is valued for its granulometry and its adhesive character.

When expressing tannins, as with alcohol, we must also distinguish the two dimensions:

Touch: Grainy (dusty, doughy, sandy, grainy) and sticky

Chemical: astringency and bitterness.

We propose a complete methodology to define the tannins. Firstly, from the tannic intensity of astringency, and secondly, from the precipitate and its drying by definition of the reactivity of the tannins:

- Green or young: tannins reactive against oxygen. They require oxygen during aging to be able to evolve. Without oxygenation work (slower than occasional) these green tannins cause the wine to reduce.

- Hard: ideal tannins to be able to bottle without risk of closing the wine. This is the optimum maturity of the tannins, desirable at the end of the aging process.

- Dry: stable tannins, without any reactivity, coming from the vineyard, extraction or late excess oxygenation. The only way to decrease astringency is to eliminate them by clarification or to mask them by coupage or additives (polysaccharides).

The model developed by the Institut de Degustación (CQFD of Maurice Chassin), the center with which we work, is the one that allows every technician a technical interpretation of perception to be able to propose, for example, aging or clarification work.

Thus, in 1993, Patrick Ducournau and Maurice Chassin developed with Oenodev a microoxygenation monitoring model based on the definition of the evolution of green tannins into hard tannins and the obsession of never getting to oxygenate dry tannins.

The assessment of the fat vs structure ratio allows for a clear idea of the aggressiveness of the wine in the mouth or its harmony, this being the highest criterion for evaluating the wine by the consumer. In this case, you are not concerned with defining the reactivity of tannins, you are only interested in expressing the aggression of the structure on your mucosa based on the fat vs structure balance. Therefore, the power of the wine fat must be considered when masking the structure.

We consider 3 hypotheses:

- High fat: the structure is not perceived. We are talking about heavy wine due to lack of body.

- Harmony between fat and structure: the structure is only perceived when spitting. It is ideal for being able to drink wine on any occasion.

- Aggressiveness of the structure due to lack of fat or excess tannins: in this case wine is consumed exclusively while eating to take advantage of the fat in the food.

Technically, in addition to the tannic style, it is important to define the harmony or aggressiveness of the wine in order to act, either by lowering the structure or increasing the fat depending on the style of wine that is intended to be proposed to the final consumer.

Fortunately, wine contains its own or added polysaccharides that limit the reaction between tannins and proteins. Some of these polysaccharides (pectins) form tertiary complexes with the tannin-protein precipitate with better solubility. Other polysaccharides (such as arabic) mask tannins that cannot bind with proteins.

In any case, it is important to consider that, depending on the polysaccharide, the interaction with tannins changes with the amount, molecular weight and length of the monosaccharide chain. This means that, when testing the inhibition of dryness by adding enological additives, it is important to vary the products (glucose, derived from yeast or gums). Practically, we often see the opposite effect: increase in sweetness at the start and increase in dryness at the end, which we call the “contrast” effect. The greater the softening power, the greater the contrast effect, especially in the case of structured wines.

It is also interesting to take into account the dryness potential per variety.

We can classify varieties according to the risk of appearance of dryness, and also relate it analytically to the percentage of tannins bound with gallic acid. We see that, statistically, Garnacha has more astringent tannins with a higher percentage of gallic tannins compared to Syrah.

Varieties such as Pinot Noir, Nebiolo or Garnacha, have a greater tendency to dryness because they contain a higher concentration of tannins with gallic acid than other varieties such as Syrah, Tempranillo or Cabernet Sauvignon.

Production techniques such as thermo-maceration not only act on the extraction of anthocyanins, but also on the type of tannins depending on the temperature. With more heating, more extraction of tannings from the seed, the winemaker can made a good decision about the heating temperature.

Continue reading The dryness of red wines (part 2)

Related news

The dryness of red wine (part 2)

In a previous article we analyzed the dryness of red wine caused by the alcohol and tannins.