There are many factors involved in the identity of a wine: soil, climate, standard, variety, driving system, vigor, load; in addition to the level of maturity, composition and health status at the time of harvest.

AGROENOLOGY seeks to understand all these factors to combine them in a profitable and sustainable balance that will lead us to our defined wine profile.

The soil, in addition to the physical support of the vineyard, is responsible for its mineral nutrition and hydration. We are going to discuss some of its characteristics and how they influence the profile and identity of the wine.

The texture is the indicator of the "physical fertility" of the soil, it conditions the root development of the vine and therefore the supply of water and nutrients.

Sandy soils are not very compact and facilitate root penetration, but have little water and nutrient retention capacity, organic matter degrades rapidly and rapidly releases nutrients. They are hot soils that advance the maturation of the grape.

Clay soils usually have a significant humic reserve with a high capacity to retain water and nutrients, but they hinder the development of the root system because they are compact and plastic. They are cold soils that delay maturation and can give high yields.

Loamy soils have intermediate characteristics to the previous ones.

In stony soils, coarse elements predominate; their fertility will depend on the quality of the fines. The thick edges give freshness and if they are superficial they improve maturation due to the light that they radiate to the bunches.

Organic matter (OM),

Old and heavily worked soils, for example in the Mediterranean arc, in Rioja or in Ribera del Duero, have relatively poor contents, from 0.7 to 1.5% on average; while for example in some Australian soils or in the Marlborough area in New Zealand this can reach levels of 6 to 7%.

The grapes that we harvest each year are not born out of nowhere, apart from the C that comes from photosynthesis, the rest of the components are obtained from the humic clay complex of the soil via the roots or from the eventual foliar fertilization, therefore the soil is depleting in nutrients and organic matter.

Changing the soil is materially and economically unfeasible, but we can take care of it, stabilize it and conserve it to ensure its survival and productivity in accordance with the objective profile. This is the objective that organic amendments meet, provided they are quantitatively and qualitatively reasoned.

Quantitative because the structure of the soil and its microbiological quality determine the consumption and assimilation capacity of OM. For example, a silty clay soil consumes and assimilates more OM than a calcareous clay soil and even more than a sandy soil. It is a good idea to only give each soil the amount that it can integrate since an excess of OM increases the demand for nutrients for its degradation and competes with the plant.

Qualitative, also paying attention to the C/N balance.

A high C/N ratio such as that provided by pruning residues and plant debris loads the plot with C with a N deficiency, which is the food for the microorganisms that are going to decompose the OM, nitrogen stress favors the “hunger of nitrogen” which is consumed for the digestion of OM and there is no availability for the plant, this translates into an increase in flavanols and phenolic acids in the grape.

MicrobiotaAlthough still little known, soil microorganisms are responsible for the degradation of organic matter and for keeping the humic clay complex, the vineyard's pantry, alive. Quality grapes need to grow in a living soil, with intense and varied microbiological activity that will take care of degrading the OM and making the nutrients available to the plant.

The sustainability of the vineyard requires keeping the soil alive, favoring an environment conducive to microbiological diversity; aeration, pH, humidity, quality OM, that is to say in addition to being well composted and having an adequate C/N ratio, it is living matter that contributes to microbiological richness. If granulation is used, it is important to do it cold, since hot granulation kills everything and leaves the compost “fried”, without microbiological activity, so integration into the soil becomes very slow.

Tillage also participates in the expression of the variety.

An intense tillage, as in the case of organic production, breaks the superficial roots that are responsible for the absorption of cations in the first stages of vegetation, giving wines with a lower pH.

Late tillage is suitable for promoting vigor since it mobilizes N reserves to improve the digestion of organic matter, it will be, for example, an adequate practice to search for thiolic profiles, provided that there is sufficient organic matter. However, it would be inadvisable if we are looking for a ripe fruit profile, since excess N favors vigor and delays ripening.

Mineral Composition

Each mineral element, macro or micronutrient, has a specific role in the physiology of the plant and in the composition of the grape. As the theory of “Liebig's barrel” expresses if one is missing nothing works well, and if one is in excess it causes imbalances.

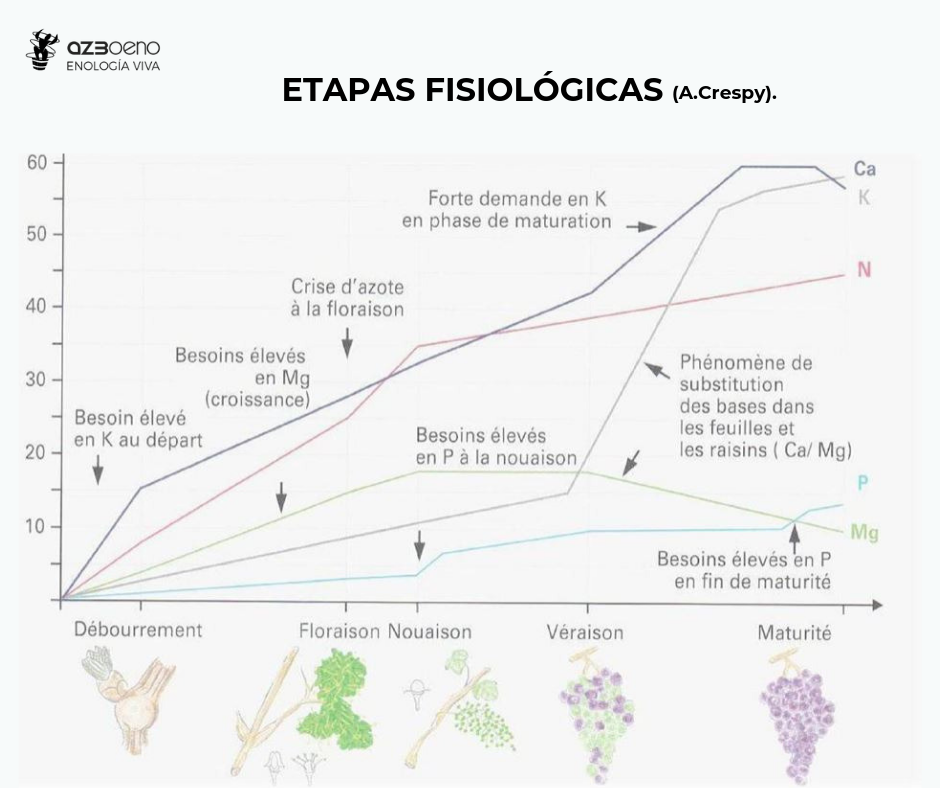

The P as an energy engine favors root development and therefore the assimilation of nutrients, it also improves resistance to water and thermal stress, for example treatment with DAP with young shoots, 3 leaves, increases resistance to spring frosts.

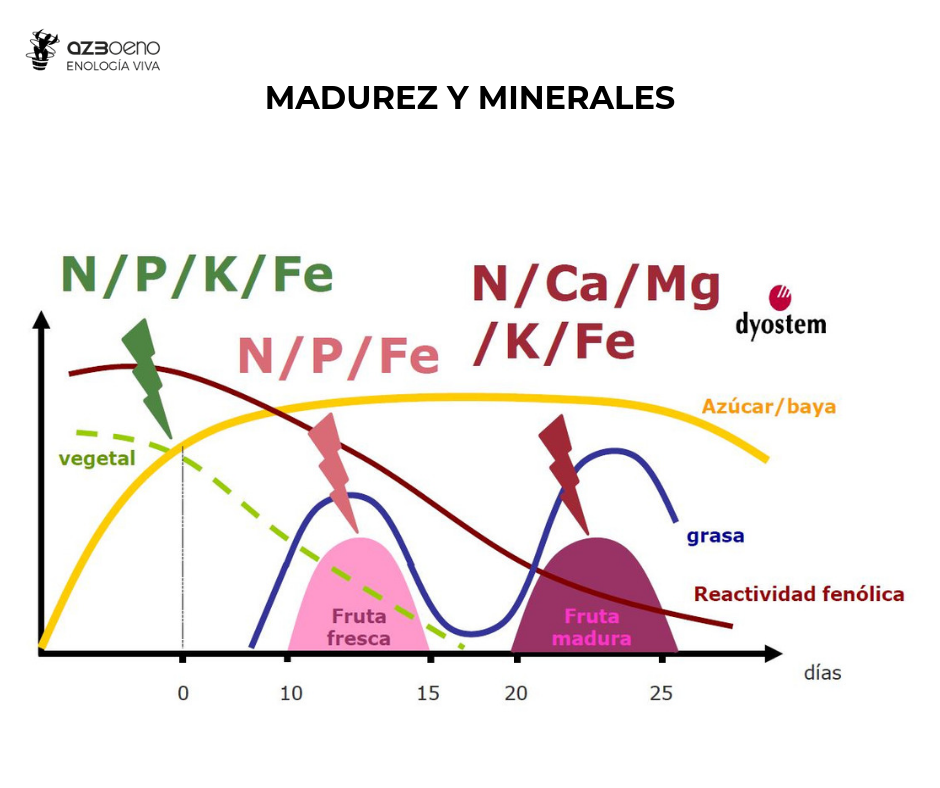

The K is a plant growth factor and favors production, but an excess causes dilution of the grape and loss of color. In addition, its assimilation competes with that of Mg, this imbalance causes maturation blockages, drying of the stalk and raisin. The base and the variety also mark different needs, for example, higher in Tempranillo than in Garnacha.

The Ca plays an important role in physiological maturity and in long maturation, as it confers resistance to the skin. It is important especially in berry size grapes about 2 ml.

Iron is necessary throughout the vegetative cycle, if it begins with deficiencies it decreases the potential of the plot.

The Nitrogenous diet impacts on multiple aspects: the synthesis of aromatic precursors, the stability of the wine, the vigor, the yield, the skin/pulp ratio and delays the point of physiological arrest. The grape requires high contents for thiol and fresh fruit profiles, and more moderate contents for ripe fruit profiles. An easy way to check the nitrogen status of the plant in key phenological stages is to measure the chlorophyll and flavanoids in the leaf;Dualex.

If we want to obtain the best expression of the identity of our wine, we need to know what happens in the soil and in the plant, to provide the appropriate nutrients for each grape profile in each phase of the vegetative cycle with a rational and sustainable strategy. This is achieved by observing, measuring and analyzing soil, petioles and shoots.

Related news

More than winemaking machines

The winemaker is the artist who observes the vineyard, interprets it and imagines the wine that could be produced from this plot.

Was it the wood or the process?

Today, we are thinking about one of the most important stages of production: the aging of the wine.

How can you save money and preserve the fruit?

NURTURE, produce, feed and educate a living entity until its full development.